Prospects for a Just Peace between Russia and Ukraine: South Africa's Potential Pathway

Source: Australian Institute of International Affairs

The Ukraine Global Peace Summit is a platform for the international community to take unified action and put diplomatic pressure on Russia. South African history suggests that achieving a fair peace for Ukraine requires Russian political leaders to condemn the aggression and compensate the victims.

The Summit for Peace in Ukraine

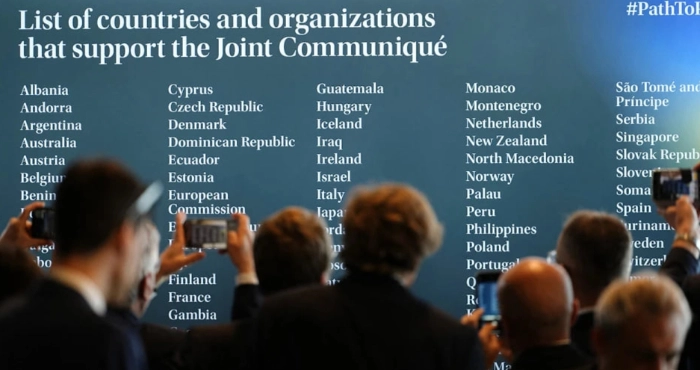

The Global Peace Summit in Switzerland, also known as the Summit for Peace in Ukraine, took place on 15-16 June and gathered representatives from 101 countries and international organisations, according to the Ukrainian Presidency. The Summit’s Communique covered three of the ten points in the Zelensky Peace Formula: food security, nuclear and energy security, and the release of all captured and deported Ukrainians, including adults and children, abducted by Russia.

The Communique, already signed by over 80 countries and international organisations, emphasised the importance of territorial integrity, which Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has violated, and called for a “just and lasting peace” rather than peace at any cost. Russia’s annexation of Ukrainian territories is particularly significant as it marks the first instance of a nuclear-armed state attacking a country that relinquished its nuclear arsenal under the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). In 1994, Ukraine gave up the world’s third-largest nuclear arsenal in exchange for security assurances from the US, the UK, and Russia, who promised to uphold Ukraine’s territorial integrity and sovereignty.

These violations have destabilised global food chains, energy and financial markets, and caused a global shift in military spending, diverting resources from social and economic development. According to SIPRI, global military expenditures reached a record high of US$2.4 trillion in 2023, a 6.8 percent increase. These expenditures are expected to grow in 2024, further diverting funds from critical developmental agendas, particularly in Africa.

South African position on Ukraine Peace Summit Communique

African countries such as Ghana, Kenya, and Rwanda were among the Communique’s signatories. However, South Africa, which also gave up its nuclear weapons and joined the NPT, participated in the Summit but has not signed the Communique. Professor Sydney Mufamadi, South Africa’s National Security Advisor, and representing South Africa, stated that while South Africa “upholds the territorial integrity and sovereignty of Ukraine,” it did not sign as “Israel is present and participating.” From 1994 until the 2024 elections, the South African government was governed by one party–the African National Congress (ANC)–and has taken the defence of Palestine as one of its foreign policy priorities.

Does not signing the Communique mean that South Africa is not supporting Ukraine? In June 2023, Cyril Ramaphosa, the President of South Africa, led an African Mission to Ukraine and Russia. The mission, led by South Africa, included leaders from six countries: Comoros, Congo-Brazzaville, Egypt, Senegal, Uganda, and Zambia. It became the first mission of African states to address a conflict outside the continent. Following the African peace mission, South Africa joined the regular meetings of the National Security Advisors and Foreign Policy Advisors on the Ukrainian Peace Formula, and co-chaired with the UK group 9 the Ukraine Peace Formula–the Regional Security Architecture.

The 2024 elections marked the first time since South Africa’s independence in 1994 that the ruling party, ANC, did not secure a majority and had to form a coalition. The Summit for Peace in Ukraine occurred when President Cyril Ramaphosa was re-elected as president of South Africa. However, this time, the president was elected by the newly established Coalition of Government Unity, which includes the ANC, Democratic Alliance, and Inkatha Freedom Party. Given the differences in foreign policy preferences among the parties, this coalition may adjust South Africa’s position on Ukraine. Parties openly supporting Russia did not join the new coalition, suggesting the government might align more closely with South Africa’s constitution, which strongly emphasises human rights and rule-based order.

Lessons from South Africa: the international community should ensure solidarity

Sydney Mufamadi, in his reflections on peace in Ukraine, highlighted South Africa’s experience of negotiating with the apartheid government despite atrocities committed against non-white South Africans. The South African government often stresses non-alignment and calls for Ukraine and Russia to negotiate, citing their own history as an example.

On 16 June, South Africa commemorated the 48th anniversary of the Soweto Uprising, a major protest led by black schoolchildren against the apartheid regime’s education policies. The police fired on the peaceful crowd, killing about 300 black youths and injuring over 2,000. The Soweto Uprising is often seen as a turning point in the struggle against apartheid, leading to international sanctions and boycotts, including the African countries’ boycott of the 1976 Olympic Games. If negotiations are always the only way, does it mean that Steve Biko, the leader of the Pan-Africanism movement killed in a South African prison in 1977, was a less effective negotiator than Nelson Mandela? Based on the logic suggested by the South African government, if anti-apartheid leaders reached a settlement in 1977 instead of 1994, many fewer people would have suffered.

The problem with this logic is that the Apartheid government was not willing to negotiate in 1977. Similarly, the Russian government does not recognise the existence of the Ukrainian identity or Ukraine as an independent country and is not willing to negotiate. The evidence of this is not only that the Russian president has adjusted his government for a long-term war, but also that Russian authorities feel free to publish maps of Russia that include the whole territory of Ukraine.

South African history suggests that several key issues were prerequisites for peaceful negotiations in South Africa and remain essential for a just peace in Ukraine:

- Condemnation and Dismantling of Aggression: Racism is a criminal offence in South Africa, and all legislation supporting racial segregation has been dismantled. Similarly, Russian political elites must openly condemn the invasion and commit to not repeating it again. Some academics describe the ideology behind the Russian war as Russian colonialism and the Ukrainian Parliament officially defined it as “Rashism,” an ideology that must be condemned.

- Compensation for Victims: Following condemnation, rebuilding and supporting the victims is crucial. In South Africa, policies were implemented to seek economic and historical justice, though their effectiveness can be debated. Russia must commit to rebuilding Ukraine and compensating for the damage caused.

The international community played a crucial role in ending apartheid through sanctions, boycotts, and diplomatic pressure, demonstrating the power of global solidarity in combating injustice. The international community should continue supporting Ukraine, applying economic and political pressure on Russia to cease its aggression.

Until Russia is ready to talk, Ukrainian soldiers are Ukraine’s best diplomats. Thanks to the daily defence by regular Ukrainians, including the 67,000 women in the military, events like the Summit for Peace in Ukraine are possible. The international community that supports rule-based order should back Ukraine’s diplomatic efforts and its army to uphold territorial integrity, sovereignty, and the right of each country to manage its natural resources.

Dzvinka Kachur is a research fellow at the Centre for Sustainability Transitions at Stellenbosch University (South Africa) and co-founder of the NPO ‘Ukrainian Association of South Africa.’ To contact authors: Dzvinka.kachur@gmail.com

Olexiy Haran is a Professor of Comparative Politics at the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy (NaUKMA). He was the founder of the NaUKMA Faculty of Social Sciences as well as the School for Policy Analysis. Prof. Haran is also the Research Director at the Democratic Initiatives Foundation, a leading Ukrainian sociological and analytical think tank.

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.